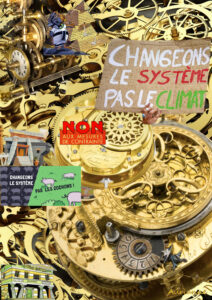

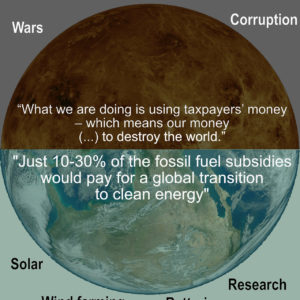

The state and the media blamed workers considered not productive enough for the loss of their factories in the 70s. For the past twenty years, they’ve been blaming this same generation for environmental pollution. It would be the people who polluted without regard for the environment. It’s the same strategy for the same end: pit one part of the population against another and divert people’s anger away from the real culprits: the industry owners and the politicians who serve them instead of representing their citizens.

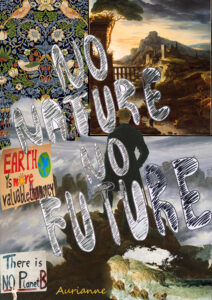

Since the beginning of industrialization, there has been resistance to protect nature.

Peasants were driven off their farms by physical violence or by burning down their homes to force them to become city workers. The population was unable to protect nature. They were repressed by the police and army.

It’s impossible to blame the population for the destruction of the environment. Many have spoken out against it. It is the decision-makers, in the hands of those who benefit in the short term from this pollution, who have forced the population to do it. It’s not true that our forefathers didn’t care about the environment, or that people are to blame for pollution.

Le Temps des ouvriers – 4 épisodes – Arte: https://educ.arte.tv/serie/le-temps-des-ouvriers-tous-les-episodes

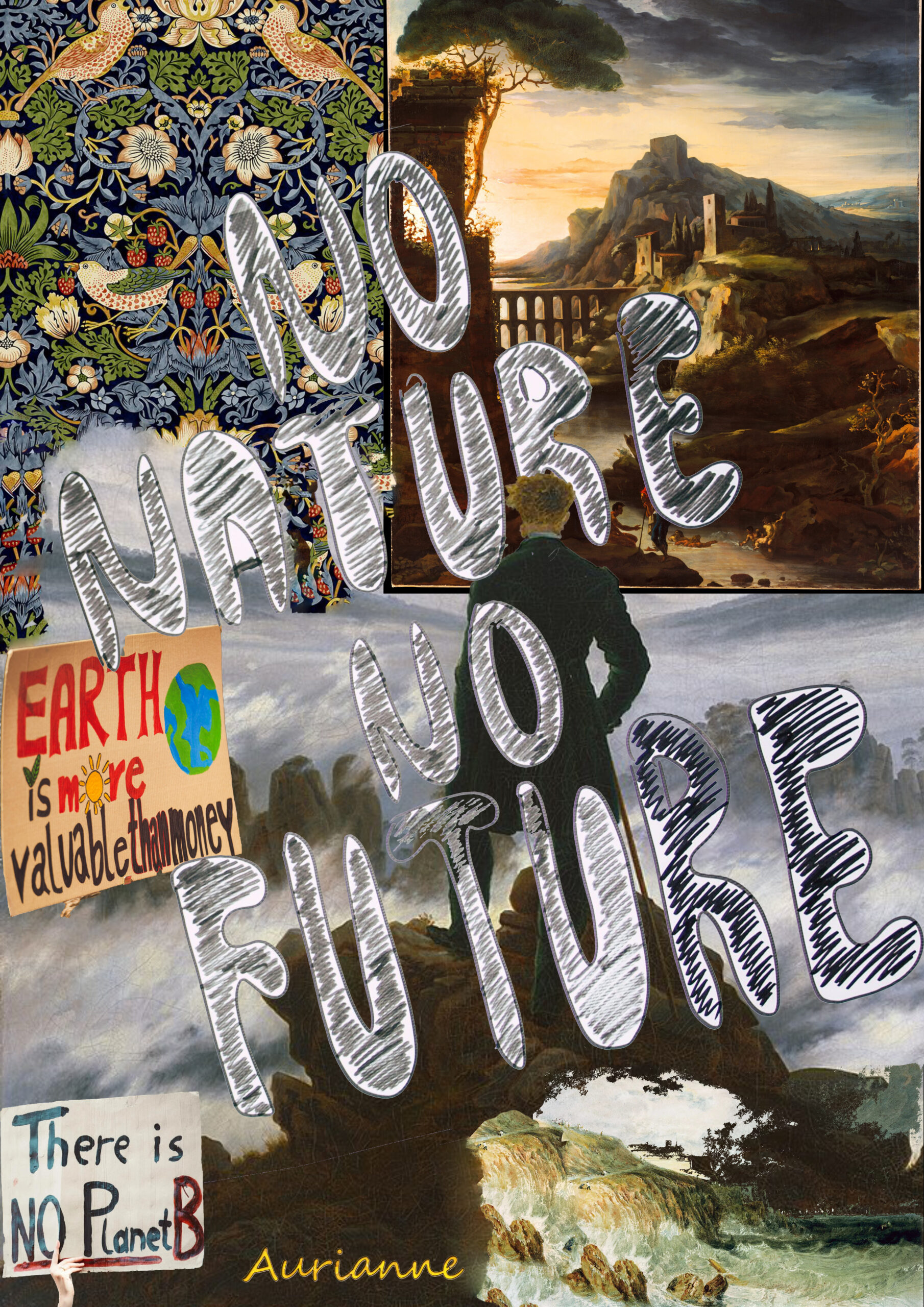

Artists have taken up the cause of nature. For example, William Morris, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Romantics such as Victor Hugo, Alphonse de Lamartine, Henri David Thoreau, Caspar David Friedrich, François René Chateaubriand, William Wordsworth, William Turner, Théodore Géricault and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

William Morris – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Morris

La nature chez les romantiques – Wikipedia: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Th%C3%A8mes_r%C3%A9currents_du_romantisme_fran%C3%A7ais

Romanticism – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romanticism

In the 19th century, workers and the poorest sections of the population suffered disproportionately from pollution, while those who could afford it moved to the greener, higher-altitude suburbs further west.

“Towards the end of the nineteenth century, concern about nature grew among wealthy, educated citizens. They form groups to protect nature (as well as culture) for aesthetic purposes in their region – Heimat or small homeland. With the rise of nationalism, the preservation of nature was increasingly put forward as a patriotic cause. Anti-modernist and anti-capitalist idealism informed some of the patriotic movement’s criticism of hedge trimming and the intensification of agricultural production, for example. The emergence of tourist interests strengthens local support, as in the Rhineland, the heart of nineteenth century tourism, or in France, against the mining of picturesque rock formations. These groups show their disagreement by writing letters to the authorities, or organize lotteries to raise funds to acquire land.”

National parks, nature protection groups, “natural monuments” and bird protection laws are emerging in Europe and the United States. This was made possible by the mobilization of the population for the preservation of nature.

In the 1930s, the naturist movement was very popular. The term “biological ecology” was born at this time. Farmers were against chemical fertilizers. They resisted from 1924 to 1947.

An Agricultural Testament – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/An_Agricultural_Testament

The Pioneers of Biodynamics in Great Britain: From Anthroposophic Farming to Organic Agriculture (1924-1940): https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/37261/1/Paull2019.BDpioneersUK.pdf

Organic architecture advocates that habitat should resemble nature.

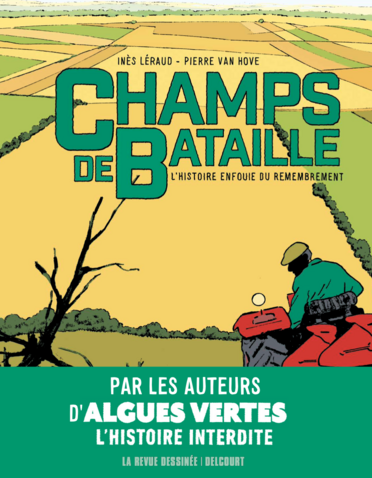

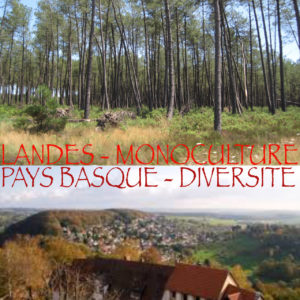

“After the Second World War, socialists “stressed that victory over capitalism would also put an end to the exploitation of nature (…) In the 1950s, socialist countries passed numerous ambitious nature conservation laws and created new national parks.” After the Second World War, France underwent land consolidation, to the benefit of productivist agriculture.” “The state redrew farmland in most of the French countryside, so that fields could be accessed by roads and easily cultivated by machines. This is known as “remembrement”. Small plots were grouped together to form larger ones. In bocage regions, hedges and embankments disappeared under the bulldozers’ blades. The aim was for the peasantry to produce more, and for France to become a world agricultural power. In the process, farm sizes are increasing dramatically, and the smallest peasants are disappearing.” Inès Léraud

Here we see “the opposition of the peasantry to land consolidation, a peasantry itself fractured between farmers who benefit from consolidation, and those who suffer from it, the “injured”. According to Inès Léraud, the policy of land consolidation was designed to serve France’s industrial expansion: the mechanization of agriculture was to enable farmers to farm larger areas with fewer workers, thus freeing up a substantial workforce for the factories. Hundreds of thousands of farms disappeared. “The number of farmers and farm workers fell from 7 million in 1946 to 3.8 million in 1962 (…) It was the biggest “social plan” France had ever seen”, explains the author. “In 1961, farmless peasants made up 70% of the workforce at the Citroën factory, built in Rennes a year earlier. A skilfully orchestrated labor transfer policy…”, continues Inès Léraud.”

“In Western Europe, older ideas dating back to the nature conservation and Heimat movements of the nineteenth century continued to develop in the 1950s and 1960s. In West Germany and Austria, museums and films celebrate traditions and picturesque landscapes. Landscape planning develops in the age of government planning. Wealthy members of society take an active part in nature conservation. Hamburg merchant Alfred Töpfer buys up land in rural areas to create “nature parks” where traditional farming practices and landscapes can be preserved, while opening them up to the public for tourist purposes”.

“The 50’s and 60’s saw the multiplication of local associations and societies for the protection of birds, nature… and throughout France the birth of the Société Nationale de Protection de la Nature et d’Acclimatation (SNPN), then in 1968 of the Fédération des Usagers des Transports (FUP) in the Paris region.” The Nature & Progrès association was created in 1964. May 68 plays an important role. Beatniks and hippies advocated a return to nature. Baby boomers mobilized for the preservation of nature and against nuclear power. The ecological question was taken up by “protest” authors, and ecological associations began to take an interest in the political struggle, linking up with other social movements. Greenpeace, for example, was founded in 1971.

Environnement : les premières sensibilisations des jeunes | Franceinfo INA: https://youtu.be/fGLXNCMP42g?si=iqYD8pyu6-0oEh2L

“Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring , published in 1962 and rapidly translated into all European languages, warns of the impact of DDT and other chemicals on human health and nature. By the late 1960s, scientists and experts were gathering alarming data on pollution, waste management and environmental destruction in every country. International organizations provided a platform for concern about these issues. Governments increasingly discussed the impact of the side-effects of growth on the quality of life of their citizens and initiated environmental policy.”

In the wake of the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Environment in Stockholm, the European Communities (EC) promulgated the first action program for the environment, laying the foundations for many future laws on air and water pollution control, and even on bird protection in the 1970s.

The environmental revolution of the 1970s globalized and politicized concerns about nature. “The early 1970s also saw new environmental movements take the place of the old nature conservation movements.”

“Traditionally, nature conservation preoccupies older, conservative people who write docile letters or petitions to the authorities, or weave a network of relationships with influential people. On the other hand, the new ecologists are influenced by the new left-wing ideas and protest methods of the 1968 student movements”: site occupations, street demonstrations, or informal ways of organizing militant citizen groups. “They stage spectacular demonstrations with the aim of gaining media coverage. Ecology also puts new issues on the agenda by translating them into environmental problems. The most salient and controversial of these was nuclear power, which was becoming widespread throughout Europe at the time, in anticipation of the growing need for electricity”.

“The fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989-1990 meant that environmental issues were eclipsed for a time by pressing social and economic problems and the transition to democracy. This is surprising, given the major role played by environmental issues in opposition to the former socialist regimes. The economic transition is advantageous for the environment because of the closure of certain polluting industries, even if it comes at the price of high unemployment. ”

Environmental protection has been a preoccupation of the population at least since the beginning of industrialization, and across all generations. It’s wrong to say that it’s a matter for current generations and that past generations weren’t concerned. It’s a myth that there’s a silent majority who want to pollute. Politicians give gifts to industrialists against the will of the people. Power serves the rich. It seeks to divide and conquer: it blames immigrants, the young, the unemployed, country folk and so on. They fear that the people are united.

Idées, acteurs et pratiques politiques de l’histoire environnementale européenne – Jan-Henrik MEYER – Université de la Sorbonne: https://ehne.fr/fr/encyclopedie/th%C3%A9matiques/%C3%A9cologies-et-environnements/id%C3%A9es-acteurs-et-pratiques-politiques/id%C3%A9es-acteurs-et-pratiques-politiques-de-l%E2%80%99histoire-environnementale-europ%C3%A9enne

“Le remembrement, une division des terres et des êtres” – Radio France: https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/podcasts/questions-du-soir-l-idee/le-remembrement-selon-ines-leraud-et-pierre-van-hove-9818632

“L’Occident et ses baby-boomers” – Radio France: https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceinter/podcasts/geopolitique/l-occident-et-ses-baby-boomers-3388560

L’écologie dans la France des années 1960-1970 – ESSF: https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article10428

– Inès Léraud et Pierre Van Hove – Champs de bataille, l’histoire enfouie du remembrement, aux éditions Delcourt, dans La revue dessinée.